Last update: February 18th, 2024

Abstract

The result of this research is a proposal with the purpose of helping overcome the current Venezuelan crisis via the creation of new companies with a localized model of co-determination, based on the German dual co-determination approach. Its feasibility was corroborated by analyzing the relevant laws and a law project on co-determination in Venezuela.

Keywords—company expropriation, corporate governance, corporate transparency, employee participation, fixed currency exchange rate, Venezuelan crisis, vicious circle of inflation, worker participation

I. INTRODUCTION

This article focuses on how worker participation in corporate governance might help reduce the magnitude of the crisis in Venezuela.

To do so, a brief description of the current Venezuelan situation is presented, followed by an introduction to worker participation, and successively concentrating on the German dual co-determination model. Next, the Venezuelan law project on worker participation and applicable laws are analyzed to determine if co-determination in Venezuela is legally feasible. Having established both the theoretical and legal backgrounds, a localized governance model is proposed. Afterwards, the conclusions and recommendations for future research and implementations are presented and the article closes with a reference list.

Due to time limitations, this research focused mainly on the German co-determination model and not all of those available worldwide.

II. VENEZUELAN SITUATION AND CRISIS

Since it’s basically impossible to describe any country’s situation in a few paragraphs, only the most relevant aspects are considered, in a very punctual manner.

Venezuela has historically been a monoproductive country, in the sense that most of its exportation offer consists of a very limited set of products. This makes it very vulnerable to fluctuations in the prices of these products in international markets [1]. When prices are high, wealth abounds. When they’re low, crises abound.

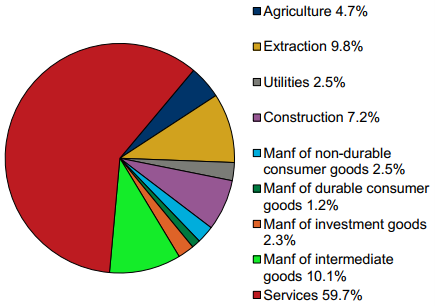

Throughout the 19th century, Venezuela exported coffee and cocoa. During the 20th and 21st, fossil fuels [1]. In fact, nowadays its economy is mainly composed of services (59.7%) and goods manufacturing (16.1%), while the largest industrial sectors are those related to oil and natural gas extraction, and their respective derivatives [2]. It must be said that Venezuela holds the world’s largest oil reserves [3].

Since 1999, year in which the Revolution rose to power with the now defunct President Hugo Chavez, the country’s main political factions have been classified as officialism and opposition. Although a third group, to which much importance hasn’t been given, has grown significantly in recent years: that of political renegades. Venezuelans have lost their hope in politicians.

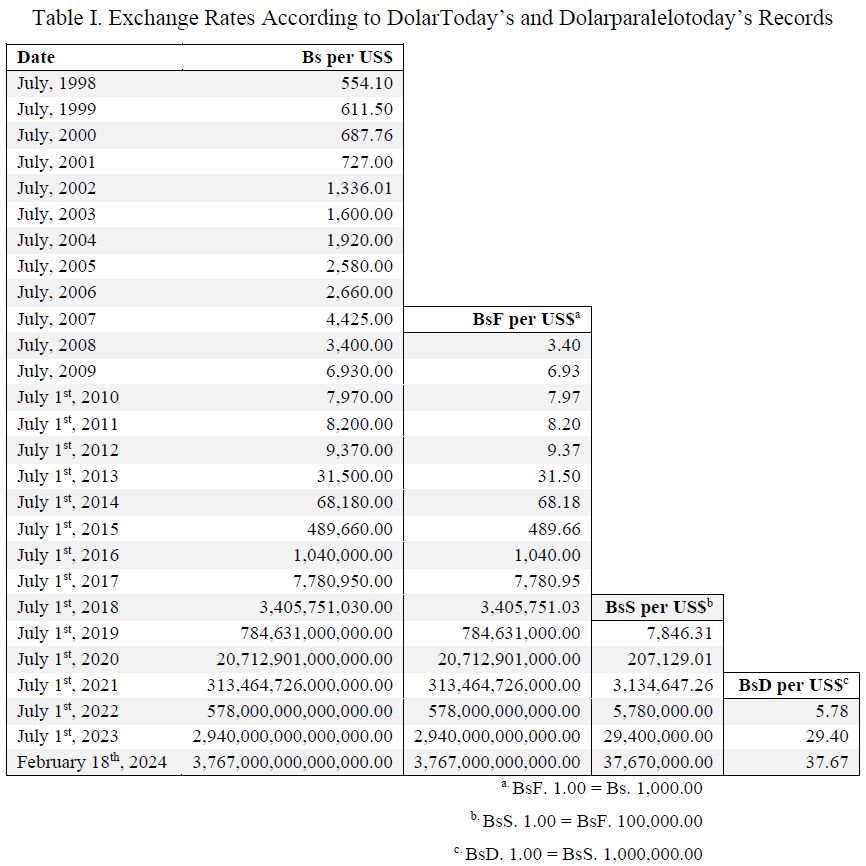

After a failed coup d’état in 2002 and several months of indefinite strike, the government established a fixed currency exchange rate (USD $) on February 5th, 2003. This meant that people and companies couldn’t just go to a bank with the local currency (Bolívar [Bs], then Bolívar Fuerte [BsF], and now Bolívar Soberano [BsS]) bills and ask for the equivalent in a foreign one. From this moment on, a request had to be filed at the bank, which was then forwarded to a government entity (CADIVI [SITME, SICAD], CENCOEX [SICAD II, SIMADI, DICOM, DIPRO]), that approved or rejected it, and returned it to the bank and requestor [4] [5]. Since the percentage of approved requests diminished with time, a black market was born and grew quite quickly (see Fig. 3 and Table I). The respective exchange rate has been published, ever since, in websites such as DolarToday.com and lechugaverde.com (which doesn’t exist anymore).

Throughout the years, the government has applied several exchange policies, which include prioritizing food and medicine, via lower rates than those for travel and online shopping, and/or auctioning the foreign currency in bulk. One of the consequences of such a multiplicity of rates is that several fly-by-night companies were created with the main, or sole, purpose to obtain the foreign currency at the lowest rate and transfer it to foreign bank accounts [6] or resell it in the black market, reapply for the preferential rate, and repeat the cycle.

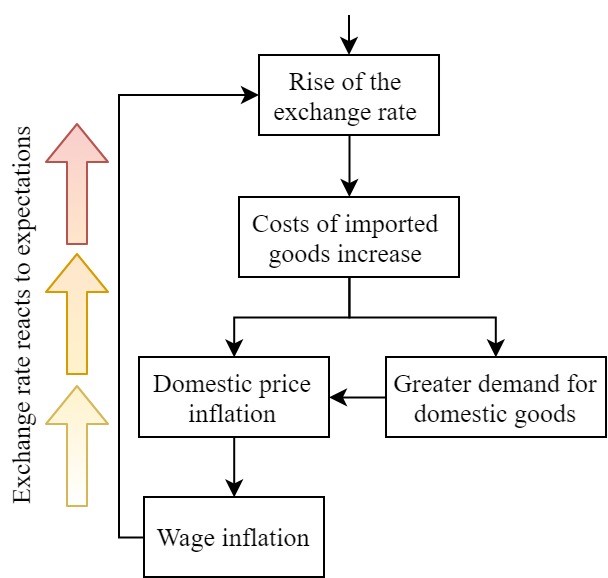

These economic results are in line with the vicious circle of inflation and depreciation [8], which begins with a monetary shock that produces an immediate and unexpected rise of the exchange rate. Successively, the costs of imported goods increase, in terms of the local currency. Consequently, domestic prices rise and so does the demand for domestic goods, which in turn elevates domestic prices even more. Afterwards, wages are increased in an attempt to compensate said inflation. If the exchange rate then reacts as expected, this vicious circle will iterate increasingly faster, as illustrated:

An attempt to break said cycle was the establishment of fixed “fair” prices for certain products [9] [10] [11] (e.g. food, medicines, school supplies, fuel, car batteries, and hygiene and baby care products). Although, many companies perceived these measures as a significant reduction of their earnings and, in some cases, as losses, so they decreased, or even eliminated, the production of such goods. At this point, the government imposed minimum production targets for these companies and expropriated more than 500 businesses [12]. These circumstances led to the creation of another black market, as in the aforementioned currency case.

However, the illegal “regulated” product resale has remained the most profitable business in Venezuela, with earnings of up to 100 times the “fair” price (10,000%) [13]. These products are also being illegally exported and resold in Colombia (contraband [14]) at prices lower than those found in such market, that still are much higher than those in Venezuela [15].

For several years, workers have left their jobs and dedicated themselves in full to these activities [16]. Yet, who can blame them if, as minimum wage earners, they’d have to work for forty-four months, from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM, Monday through Friday, to pay a one-month market basket [17]. Unsurprisingly, some repercussions of such an unpurchaseable basket are starvation, prostitution, and death.

According to a study performed during the first quarter of 2017, 1.5 million people ate trash [18] out of a population of 31,977,065 [19]. Newspaper articles indicate that around 9.6 million Venezuelans eat two or less meals a day [20], 4.5 million eat once a day, maybe even once every two days [21]. Another source quotes that “33% of the children have an irreversible growth disorder, consisting of both physical and mental damages, with which they’ll have to live for the rest of their lives” [22]. Moreover, 280,000 children could die of malnutrition [21].

In average, one child dies every day [23].

“Sex for food: Venezuelan girls who prostitute themselves to satisfy hunger” is the title of another article [24], which is self-explanatory.

Meanwhile, the one-year school supply basket (supplies, textbooks, and uniforms) costs 452.6 minimum monthly wages (~37 years) [25], reaching a 50% school dropout rate [26]. The transportation system has also decayed, with only 10% of the units still operating [27] and the rest being replaced in an improvised manner by dog carts [28].

“At least one patient dies per day due to a lack of medical supplies” [29] is another self-explanatory headline.

So, if wages don’t even cover the most basic needs, to a point in which workers essentially pay to work, because the total expense necessary to perform their duties (food + clothes + transportation + health) is much greater than the economic retribution received in exchange, why should anyone work and, more important, how can Venezuela recover?

A. SITUATION IMPROVEMENT

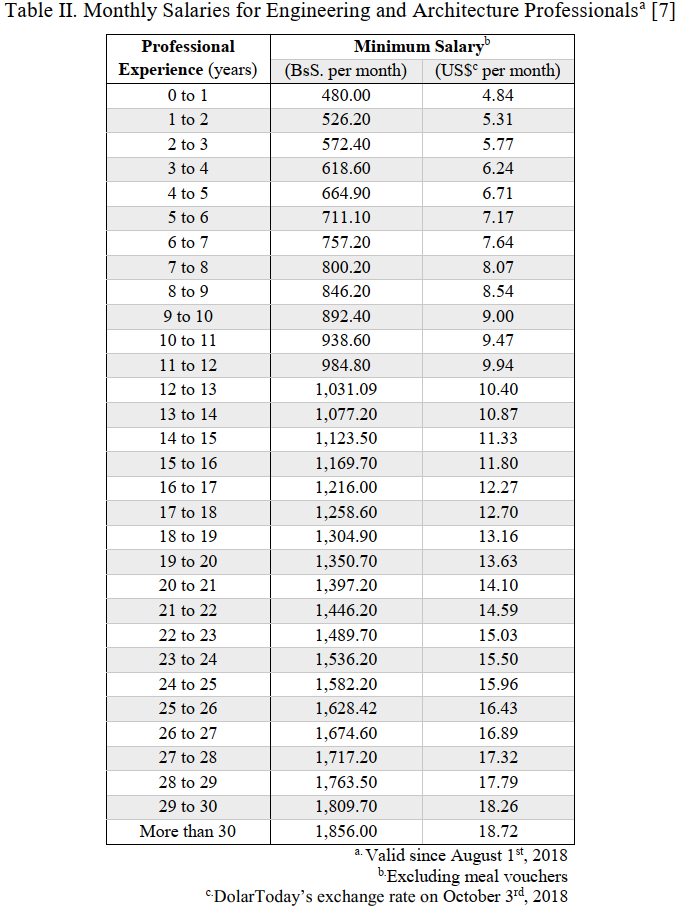

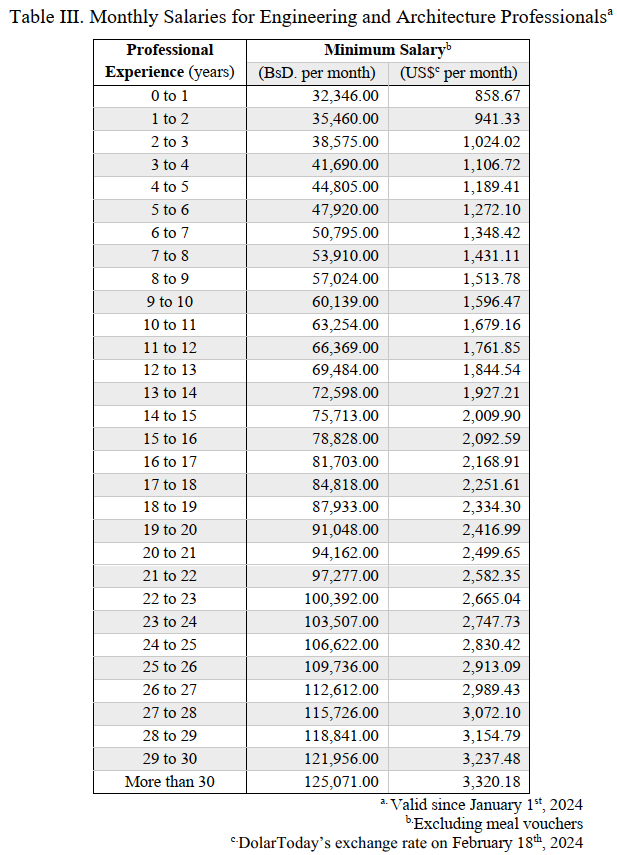

As may be observed by comparing the two following tables, the salary situation seems to have improved between 2018 and 2024, at least from the engineers’ and architects’ perspective.

The following values were obtained by applying the exchange rate of October 3rd, 2018 to the monthly wages for Engineering and Architecture professionals [7]. Although this is the main salary reference for said professionals, the actual amount most companies pay is usually lower.

The following values were obtained by applying the exchange rate of February 18th, 2024 to the monthly wages for Engineering and Architecture professionals. Although this is the main salary reference for said professionals, the actual amount most companies pay is usually lower.

III. WORKER PARTICIPATION

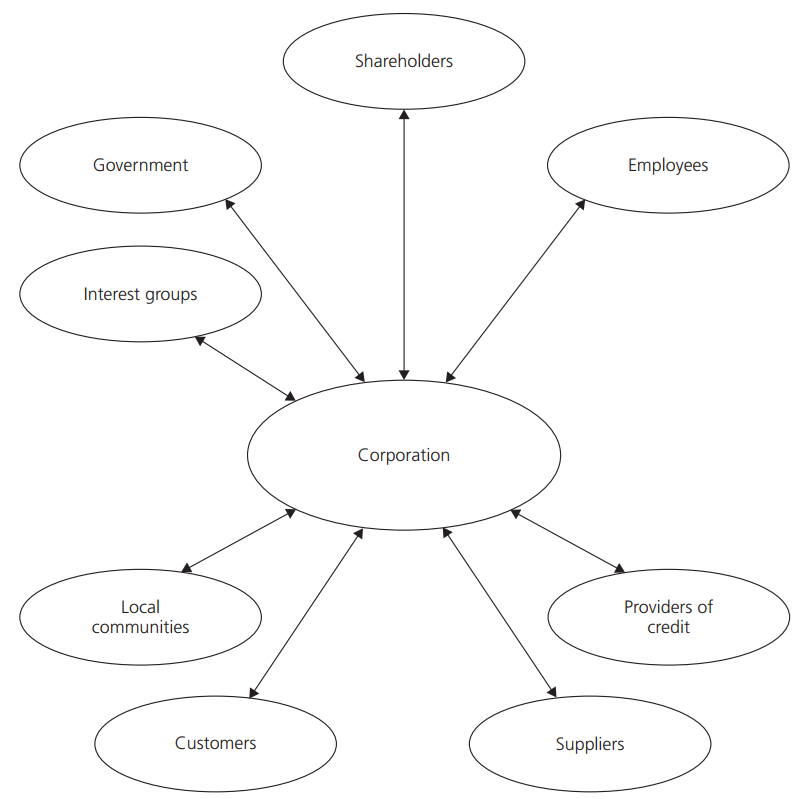

Sebastian Sick indicates that the “worker participation model helps balance the interests of the different stakeholders involved” [30], who are illustrated in the following figure.

Hence, this model prioritizes long-term social wealth over short-term profits for shareholders and managers, i.e. society over capital or stakeholder value over shareholder value. This way, “not only shareholders, but also workers, other citizens and the community at large have an interest in the good governance of companies” [32], in contrast to other models in which

The labour contract assigns control over the goals of work to the ‘purchaser’ of human capacities; it is thus -politically- a contract of subordination. The goals, content and purposes of work are in the hands not of the workers themselves, but of those who organize the labour processes (usually in accordance with market principles). [33]

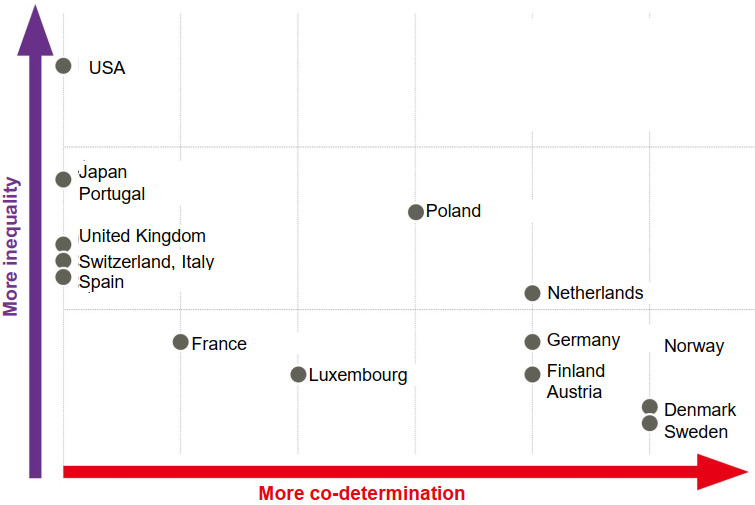

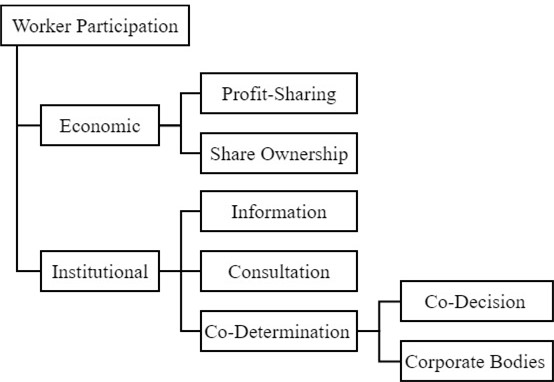

As for the countries (Fig. 6) supporting worker participation, each has adapted such model to its own requirements, possibilities, and convenience, thus spawning different localized versions with variating degrees and means of stakeholder participation in corporate governance. More precisely, said involvement may be categorized as economic and/or institutional (Fig. 7).

In the first case, they may benefit from profit-sharing and/or share ownership.

In the second case, they may have the right to be informed (downward communication) or consulted (upward communication) about certain business matters. This, however, is a particularly passive interpretation of “participation.” Co-determination, instead, gives workers a much more active role, via co-decision and participation in corporate bodies.

A. Co-determination in Germany

Of particular interest is the German co-determination approach, or “Mitbestimmung,” which gives workers the right to participate in decisions that may affect them and to be kept informed about the company’s activities [31]. According to the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs [36], the objectives of this model are: equality of capital and work, democracy in the economy, social development, and control of economic power.

In fact, in order to achieve the workers’ involvement, new corporate bodies had to be defined, in addition to the relationships among them. Since in Germany all of these change according to the company type, number of employees, and industry, this paper focuses on the dual co-determination model [37] for the GmbH (Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung: company with limited liability), that has 2000 or more employees, and isn’t in the coal, iron, or steel industry. Specifically, this kind of company is regulated by the Co-Determination Act of 1976 and the Works Constitution Act of 1972.

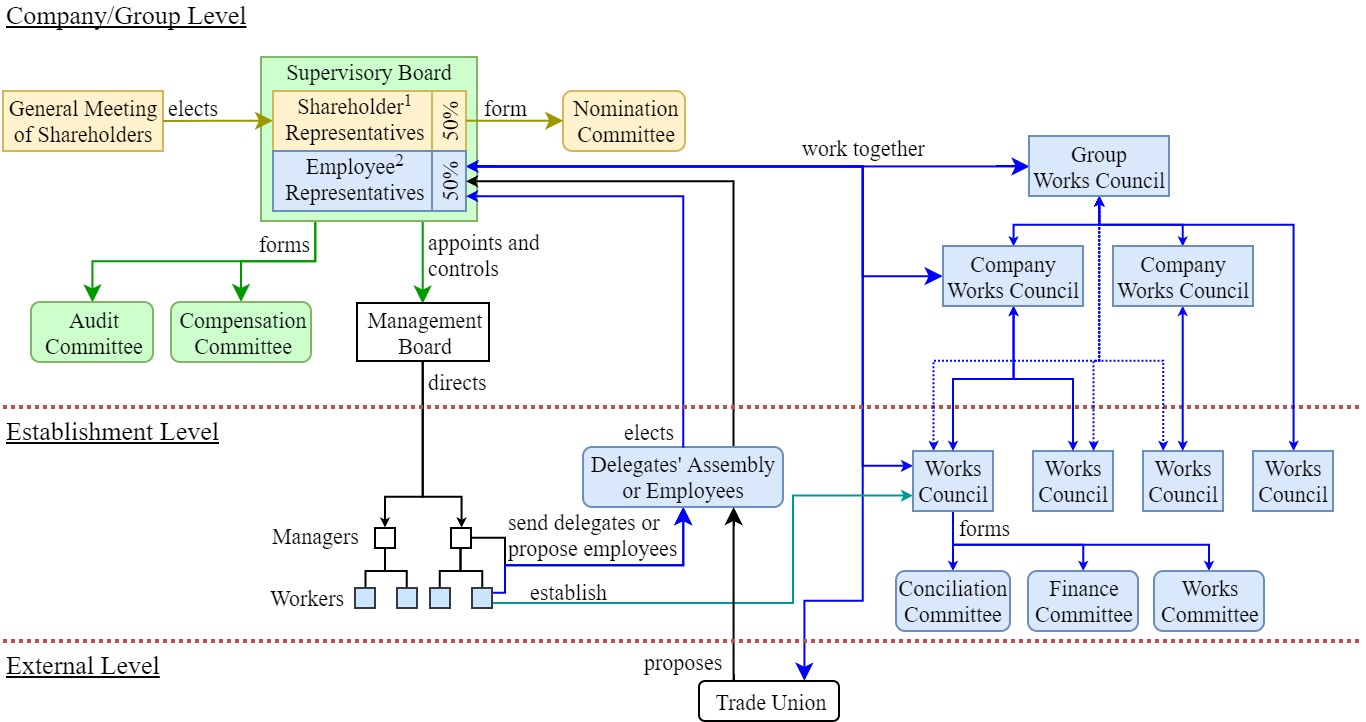

The main governance bodies are the General Meeting of Shareholders, Supervisory Board, Management Board, and Works Council (Fig. 8). The latter lies at the establishment level, where technical matters are settled, while the other bodies, at the company/group level, where economic and other kinds of objectives are pursued [30].

Half of the Supervisory Board’s members, including its chairman, are elected by shareholders at the General Meeting, while the other half, by employees or their delegates at the Delegates’ Assembly. This last half is composed of employees without any labor union or works council affiliation, trade union representatives that aren’t company employees, and managers [37]. Another aspect to consider is that, even though both sides have the same number of representatives, the chairman decides the outcome when there’s a tie. Hence, “this kind of incomplete parity-co-determination is referred to as ‘near parity-co-determination’” [38].

1 In case of a tie, the chairman has an additional deciding vote.

2 Employee representatives include managers, workers, and external trade union representatives.

As of its functions, the Supervisory Board:

- Appoints and dismisses members of the Management Board, in addition to setting their salaries [37];

- Supervises how the Management Board handles the business, scrutinizes its annual accounts and annual report, and prepares its own report for the General Meeting of Shareholders [39];

- Directly influences the company’s/group’s strategy and fundamental corporate decisions, for instance “stake acquisition and divestment, construction or stoppage of means of production, and significant indebtment undertaking” [30];

- Approves or rejects major decisions of the Management Board [37], like strategic realignments;

- Ensures there is a long-term succession plan [31];

- Makes sure confidentiality is kept for sensitive matters [39];

- Collaborates with the Trade Unions and all the levels of the Works Council structure [39].

- Delegates some of its functions to other committees, such as the Audit, Compensation, and Nomination Committees [31].

The German Corporate Governance Code recommends the creation of an Audit Committee to address the accounting control, “the monitoring of … the effectiveness of the internal control system, the risk management system, the internal audit system, the audit and compliance” [40]. It also suggests the creation of a Nomination Committee, composed solely of shareholder representatives, with the purpose of proposing suitable candidates to the General Meeting of Shareholders for the Supervisory Board’s future administrations. Meanwhile, the Compensation Committee is meant to help establish the Management Board’s members’ compensation, which should favor sustainable growth and hinder undertaking unnecessary risks, while that of the Supervisory Board’s members is determined at the General Meeting of Shareholders [31].

In turn, the Management Board is in charge of managing the enterprise, regularly coordinating its strategic approach with the Supervisory Board, and submitting the annual balance sheet and income and cash-flow statements to the General Meeting of Shareholders. It also ensures that the law and the company’s internal policies are followed, via a Compliance Management System, and develops risk management plans and activities, which it then reports to the Supervisory Board. Additionally, the Management Board handles the public disclosure of relevant information that might affect the company’s activities.

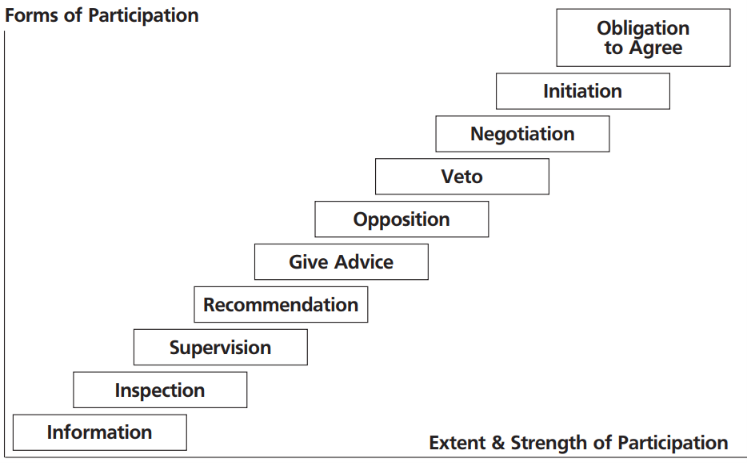

With respect to the Works Council, it’s the body closest to the employees. More specifically, both wage-earners and salaried employees are there represented, and meetings are held during working hours. As of its rights, they’re illustrated in ascending order of extent and strength of worker participation in Fig. 9.

For example, a Works Council may exert its right to negotiate on matters like:

- Order and operation of the establishment and employee conduct;

- Working time, breaks and distribution of working hours;

- Temporary reductions or extensions to the regular working hours;

- Time, place and payment form of remuneration;

- Principles of leave arrangements and schedules;

- The introduction and use of technical devices to monitor the behavior or performance of employees;

- Protection of health and accident prevention; and

- The form, structure and administration of company social services [39].

For support, the council may form Conciliation, Finance, and Works Committees.

The Conciliation Committee helps both the Works Council and the employer settle differences and reach agreements; each party appointing an equal number of advisors and electing one chairman to lead the committee.

The employer must promptly and fully inform the Finance Committee, which in turn reports to the Works Council, about relevant financial matters. Both Page [39] and the Works Constitution Act (Section 106, par. 3) enunciate the following:

- The economic and financial situation of the company;

- The production and sales situation;

- The production and investment program;

- Rationalization plans;

- Production techniques and work methods (especially the introduction of new methods);

- The discontinuation of operations or closure of establishments;

- The amalgamation or split-up of establishments;

- Changes in the organization or objectives of establishments;

- Other events or proposed changes which may involve substantial disadvantages for employees.

The Works Committee helps with the daily operations of the Works Council, like setting up meetings with the employer.

Finally, Trade Unions, while having more bargaining power than nonunion workers, negotiate collective bargaining agreements and contribute with their knowledge and experience on the business sector.

When a company has more than one establishment, a Company Works Council must be formed with the sole purpose of handling issues that concern multiple establishments and can’t be solved by the individual Works Councils. Similarly, a Group Works Council may be established to deal only with matters that affect two or more companies of the same group. Since the roles played by each of the councils don’t overlap, but instead supplement each other, none is superior to the other [39]. In fact, the members of the Group and Company Works Councils are all Works Council delegates [38].

B. Co-determination in Venezuela

As of Venezuela, the Constitution of 1999, Article 70, states that co-determination is among “The means of participation and protagonism of the people in the exercise of their sovereignty, … regarding social and economic matters” and that “The law will establish the conditions for the effective operation” of such means [41]. For this purpose, the Law Project on Worker Participation in Public and Private Companies’ Management (Proyecto de Ley de Participación de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras en la Gestión de Empresas Públicas y Privadas) was submitted to the National Assembly (highest level organism representing/enacting the Legislative Power; may be compared to a parliament or congress in other countries) in 2005. However, it was never approved and unfortunately the author couldn’t find a copy to analyze in this section. Nevertheless, several key points are mentioned in a few articles and research papers.

This law project was intended to take the officialist party’s motto of “participatory and protagonistic democracy” [41, p. 1] into the companies by empowering workers to play a protagonistic role in management. In fact, Bermúdez and Prades [42] paraphrased part of its first article by indicating that “the principle of participation and protagonism implies a democratization of decision-making, participation in management at all hierarchical and organizational levels, and access to all the operational, legal and financial documentation to guarantee the correct and efficient execution” of said decisions, while enforcing the adoption of an “ethical behavior and transparent management of the companies’ financial and operational resources” [43].

In the public sector, co-determination could’ve been established with an agreement among workers and the employer (Art. 13), in those companies of which the State possessed part or all the property (Art. 1). In the private sector, it would’ve been instituted when (Art.14):

- The Shareholders’ Assembly so determined;

- A company was declared of public use;

- It was declared that a company owned non-operating assets that could’ve been recovered for employment generation;

- A company declared bankruptcy, or the respective judicial process began;

- A company closed its operations illegally or without justification; and

- A company was, or had been, subject to incentive plans, preferential credit policies or fiscal or parafiscal benefits by the State [42].

As of the Board of Directors, it would’ve been paritary (Art. 2), consisting of worker representatives (holding 50% of the votes) and shareholder representatives (holding the other 50%), including the board’s chairman who would’ve held the deciding vote in case of a tie. So, in the end, it would’ve been a near parity-co-determination. The worker representatives would’ve been elected directly in a universal and secret manner, under the supervision of the National Electoral Council (highest level organism representing/enacting the Electoral Power).

Rivero [43] considers that the Law should “foresee the creation of a ‘Statute for [Workers’] Participation in Management,’ which is transparent, applicable, progressive and auditable, in order to establish the minimum conditions” of co-determination; and includes and regards “job descriptions, delegation of authority, co-determination operative practices, [and] quality policies”.

In 2012, the Labor Law [44] was reformed and a couple of articles related to worker participation in management was added:

Art. 497: The works councils are expressions of the Popular Power for protagonistic participation in the social process of work, with the purpose of producing goods and services that satisfy the needs of the people. The forms of worker participation in management, as well as the organization and operation of the works councils, will be established in special laws.

Art. 498: The works councils and trade unions, as expressions of the organized working class, will develop initiatives of support, coordination, complementation and solidarity in the social process of work, aimed at strengthening their consciousness and unity. The works councils will have their own attributions, different from those of the trade unions contained in this Law.

So, putting together said current and proposed laws, the resulting co-determination model might seem somewhat similar to the previously illustrated German model. Works councils and trade unions are present, in addition to the inclusion of worker representatives at the board level. However, a Supervisory Board hasn’t yet been stipulated. Hence, the Board of Directors would perform both managerial and supervisory functions.

In practice, the government intervened in the managerial and/or property structures of companies that were in one of the previously listed situations, empowering workers with varying implementations of co-determination, as no standardizing law has yet been published. In companies like CADAFE and SIDOR [45], workers detected that the management deliberately tried to hinder their participation initiatives [43] [46]. It must be said that, in some cases, the government’s intervention [47] might’ve caused additional organizational conflicts [48]. Another aspect to consider is that many of these companies depend highly on the government’s financial support [48].

IV. PROPOSAL

While the law project and its backers gave a lot of emphasis to the modification of existing companies, due to the country’s situation at that time, the author intends for this proposal on co-determination to be applied to newly created companies, thus avoiding the managerial opposition and syndicalist lobbying [49, pp. 7, 10] ordeals, and enacting solutions efficiently and effectively to respond to the country’s most pressing matters.

This proposal ratifies, and is based on, the German dual co-determination model, as it allows a high degree of worker participation in corporate governance and there doesn’t seem to be any law in Venezuela that prohibits its use. However, additional measures must be taken to reduce the level of corruption inside companies.

Hence, certain aspects of the Supervisory and Management Boards shall be opened to the general public, beyond the essential documents (e.g. balance sheet, financial and income statements, quarterly reports). In other words, it’s expected for the public to play an active role in corporate governance.

It can’t be stressed enough: one child dies every day, in average [23].

So, society as a whole shall help grow and simultaneously monitor these new companies to avoid any kind of corruption, embezzlement, and squandering of funds and resources; thereby assuming part of the Audit Committee’s responsibilities.

Initially, each of these new companies will focus on specific sectors in crisis, or that are crucial to overcoming the national crisis, taking underdeveloped areas (e.g. towns) into account. This shall be explicitly stated in their missions, visions, and values. It must be clear that, in the short and medium terms, these companies are committed to solving the crisis and, in the long term, to developing the country.

Ideas and results shall corroborate such motivation, but without the appropriate results, the rest is pointless.

Therefore, “transparency” shall be among the corporate values. Externally, for the aforementioned reasons. Internally, as a prerequisite for co-determination and employee welfare.

For instance, every worker shall have access to the list of company salaries per level. As a result, these will be more commensurate, particularly those of the board members, and there won’t be two employees in the same level with different salaries.

With respect to work hours, they shall be respected, and overtime appropriately compensated. However, working overtime shouldn’t be necessary due to modern techniques, according to Bertrand Russell [50], and should in fact be discouraged. The Works Council shall see to it, among its other responsibilities.

As of the presence of worker participation organisms throughout the company’s growth, workers shall be represented in the Supervisory Board from the beginning, while Works Councils shall be constituted when more employees are hired. Also, the Supervisory Board’s chairman’s deciding vote, in case of a tie, shall be duly and clearly motivated and published on the company’s stakeholder relations website.

Such website shall include sections dedicated to each kind of stakeholder, including workers and financial investors, and provide them with interaction and participation mechanisms. For example, one section may contain all the dealings and reports made by government officials in relation to their visits, indicating their purposes and outcomes. Additionally, a software solution shall be created to support the workers’ participation and respective organisms.

Finally, since the vicious circle of inflation and depreciation may be broken by increasing the supply of domestic goods and incentivizing foreign investors [8], if the new companies saturated their respective markets with quality products and services, domestic prices would decrease, illegal resellers/smugglers wouldn’t find their activities profitable any more, the costs of imported goods would probably decrease, as the prices of the domestic options diminish, and the exchange rate would decline, since the demand for foreign currencies would weaken. The increased level of transparency should also help attract investors and funds, as concluded by Gelos and Wei: “We find relatively clear evidence that international funds prefer to hold more assets in more transparent markets… [and] there is some modest evidence that during a crisis, international investors tend to flee more opaque markets” [51].

V. CONCLUSIONS

Having presented the Venezuelan situation, introduced the German dual co-determination model, and analyzed how co-determination has been, or might be, implemented in Venezuela, a new localized governance model was proposed.

Unfortunately and unexpectedly, the Venezuelan Law Project on Worker Participation in Public and Private Companies’ Management couldn’t be found and, although it doesn’t really have any impact on the proposal, it would’ve been nice to see its structure.

Nevertheless, by adopting the German model and enhancing the levels of transparency and societal participation, focusing on specific industrial sectors to provide definitive solutions to the crisis, and producing/offering high quality products/services, the situation in Venezuela should change for the better.

To sum up, the proposed model isn’t just about increasing the net income, or “making money.”

It’s about people going to work every day knowing that by giving their best, they’ll be helping to build a better country. It’s about managers being role models with social conscience, who lead and motivate workers to be the best they can be, while improving their surroundings. It’s about directors seeking, organizing, and performing social responsibility activities, not to appear on some newspaper or because they feel obliged by others, but because they truly want to do so.

It’s about putting food on starving children’s plates.

VI. RECOMMENDATIONS

For this model to be successful, there mustn’t be any kind of political party affiliation. The companies shall focus on solving the crisis and the nation’s positive growth and evolution. Endogenous development shall be favored, for underdeveloped areas to grow and the population density of overcrowded cities to diminish.

University participation is indispensable for all of this to work. Hence, it shall be actively, and constructively, involved. In fact, most companies should be born there, from students’ and teachers’ ideas and projects to solve the crisis.

Further research inquiries might include the following:

- How might each external (general public) stakeholder category be engaged to interact with the company and by what means?

- Could the proposed model be improved for achieving greater efficiency and efficacy levels, while maintaining the required degree of transparency and worker participation?

- Should a national organization be created for prioritizing and coordinating Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives? Should high school and university students also be involved?

REFERENCES

[1] | R. Cartay, “Las crisis económicas y sus repercusiones en la economía venezolana,” Economía, no. 11, pp. 45-54, 1996. |

[2] | “By country industry forecasts > Venezuela,” Oxford Economics Ltd., 14 June 2018. [Online]. Available: https://0-search-proquest-com.opac.unicatt.it/docview/2055139811?accountid=9941. [Accessed 25 July 2018]. |

[3] | J. Dillinger, “The World’s Largest Oil Reserves By Country,” WorldAtlas, 6 April 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-world-s-largest-oil-reserves-by-country.html. [Accessed 2 October 2018]. |

[4] | “Cronología del sistema cambiario venezolano,” teleSUR, 17 February 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.telesurtv.net/news/Cronologia-del-sistema-cambiario-venezolano-20160217-0071.html. [Accessed 25 July 2018]. |

[5] | G. Gupta, “Venezuela sets new exchange mechanism, as currency continues to slide,” Reuters, 25 May 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-venezuela-economy/venezuela-sets-new-exchange-mechanism-as-currency-continues-to-slide-idUSKBN18L03C. [Accessed 25 July 2018]. |

[6] | “Ministerio Público allanó residencias que albergaban empresas de maletín,” Vicepresidencia de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela, 27 September 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.vicepresidencia.gob.ve/index.php/2017/09/27/ministerio-publico-allano-residencias-que-albergaban-empresas-de-maletin/. [Accessed 26 July 2018]. |

[7] | “Tabulador CIV,” Distribuidora 3HP C.A., 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.distribuidora3hp.com/tabuladorciv.htm. [Accessed 3 October 2018]. |

[8] | J. Ahmad, “The Vicious Circle of Inflation and Depreciation,” in Floating Exchange Rates and World Inflation, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 1984, pp. 143-162. |

[9] | “Sundde publicó nuevos precios de productos de higiene y cuidado personal,” El Nacional, 24 November 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/economia/sundde-publico-nuevos-precios-productos-higiene-cuidado-personal_212801. [Accessed 27 July 2018]. |

[10] | “Sundde publicó nuevos precios de pasta, caña de azúcar y crema dental,” El Nacional, 23 November 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/economia/sundde-publico-nuevos-precios-pasta-cana-azucar-crema-dental_212637. [Accessed 27 July 2018]. |

[11] | “Sundde aprobó nuevo precio de la carne,” El Nacional, 8 November 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/economia/sundde-aprobo-nuevos-precios-carne_210893. [Accessed 27 July 2018]. |

[12] | J. Wyss, “Venezuelan government controls more than 500 businesses – and most are losing money,” Miami Herald, 14 March 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/venezuela/article138402248.html. [Accessed 27 July 2018]. |

[13] | J. Lafuente, “‘Bachaqueo’: el negocio más rentable de Venezuela,” EL PAÍS, 23 May 2016. [Online]. Available: https://elpais.com/internacional/2016/05/22/america/1463947040_019429.html. [Accessed 28 July 2018]. |

[14] | teleSUR tv, “Contrabando en Venezuela,” YouTube, 25 May 2015. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mqBTdigw98s. [Accessed 28 July 2018]. |

[15] | S. Palomino, “El ‘bachaqueo’ venezolano se instala en la frontera colombiana,” EL PAÍS, 30 October 2017. [Online]. Available: https://elpais.com/internacional/2017/10/27/colombia/1509121735_408975.html. [Accessed 28 July 2018]. |

[16] | L. Solano, “Zulianos dejan sus trabajos para ‘bachaquear’,” Runrunes, 8 September 2014. [Online]. Available: http://runrun.es/nacional/actualidad/152971/zulianos-dejan-sus-trabajos-para-bachaquear.html. [Accessed 28 July 2018]. |

[17] | M. Machado, “Tomás Guanipa: ‘Se necesitan 44 salarios mínimos para costear la canasta básica alimentaria’,” El Universal, 3 July 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.eluniversal.com/politica/14086/guanipa-se-necesitan-44-salarios-minimos-para-costear-la-canasta-basica-alimentaria. [Accessed 28 July 2018]. |

[18] | J. Barreto, “Alertan que en Venezuela se intensifica el hambre,” El Nacional, 17 October 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/sociedad/alertan-que-venezuela-intensifica-hambre_208128. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[19] | “Venezuela – Población 2017,” Datosmacro.com, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/demografia/poblacion/venezuela. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[20] | E. Romero-Castillo, “Hambre y desnutrición: alarma en Venezuela,” Deutsche Welle, 30 November 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.dw.com/es/hambre-y-desnutrici%C3%B3n-alarma-en-venezuela/a-41598293. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[21] | L. Vinogradoff, “Alrededor de 300.000 niños podrían morir por desnutrición en Venezuela, según Caritas,” ABC, 27 December 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.abc.es/internacional/abci-alrededor-300000-ninos-podrian-morir-desnutricion-venezuela-segun-caritas-201710250219_noticia.html. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[22] | G. Herrera, “Los látigos del hambre en Venezuela,” El Nacional, 6 December 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/crisis-humanitaria/los-latigos-del-hambre-venezuela_213243. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[23] | A. Hernández, “Un niño muerto al día: las víctimas de la desnutrición en el interior de Venezuela,” El Confidencial, 12 March 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.elconfidencial.com/mundo/2018-03-12/venezuela-ninos-muertos-desnutricion-interior_1533765/. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[24] | “Sexo por comida: las niñas venezolanas que se prostituyen para saciar el hambre,” El Cooperante, 1 November 2017. [Online]. Available: https://elcooperante.com/sexo-por-comida-las-ninas-venezolanas-que-se-prostituyen-por-un-bocado/. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[25] | “El costo de la canasta básica escolar superó el millardo de bolívares,” TalCual, 23 July 2018. [Online]. Available: http://talcualdigital.com/index.php/2018/07/23/el-costo-de-la-canasta-basica-escolar-supero-el-millardo-de-bolivares/. [Accessed 28 July 2018]. |

[26] | “Deserción escolar en Venezuela se encuentra a más del 50%,” El Nacional, 13 April 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/sociedad/desercion-escolar-venezuela-encuentra-mas-del_230872. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[27] | A. Ramírez, “Plantean subir a Bs 10.000 el pasaje a partir de mañana en Caracas,” El Nacional, 3 June 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/servicios/plantean-subir-10000-pasaje-partir-manana-caracas_238319. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[28] | V. Sequera and M. Armas, “Weary Venezuelans rely on ‘dog cart’ transports as buses succumb to crisis,” Reuters, 17 July 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-transportation/weary-venezuelans-rely-on-dog-cart-transports-as-buses-succumb-to-crisis-idUSKBN1K72BJ. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[29] | “León Natera: Todos los días muere al menos un paciente por falta de insumos,” El Nacional, 11 March 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.el-nacional.com/noticias/salud/leon-natera-todos-los-dias-muere-menos-paciente-por-falta-insumos_226421. [Accessed 29 July 2018]. |

[30] | S. Sick, “La codétermination en Allemagne: un modèle de participation des travailleurs dans le cadre d’un modèle économique coopératif,” Annales des Mines – Réalités industrielles, vol. Août 2013, no. 3, pp. 26-32, 2013. |

[31] | C. Mallin, Corporate Governance, 4th ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. |

[32] | J. Monks, “Worker Involvement In The European Company: Another Step To Realising Social Europe,” in The European Company – Prospects for Worker Board-Level Participation in the Enlarged EU, Brussels, 2006, pp. 12-13. |

[33] | U. Beck, “Paid employment: organizable solidarity,” in The Brave New World of Work, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2000. |

[34] | Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, “Why co-determination?,” 2018. |

[35] | M. Corti, La partecipazione decisionale e finanziaria dei lavoratori in Italia e in Europa, Milan: Facoltà di Economia, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 2018. |

[36] | Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Mitbestimmung. Unternehmensmitbestimmung & Betriebsmitbestimmung, 1995, pp. 5-8. |

[37] | G. Gorton and F. Schmid, Class Struggle Inside the Firm: A Study of German Codetermination, 2002. |

[38] | S. Lücking and S. Sick, “Le sfide della codeterminazione in Germania,” ERE/Emilia-Romagna-Europa, no. Nr. 16, pp. 25-34, 2014. |

[39] | R. Page, “Co-determination in Germany – A Beginners’ Guide,” Arbeitspapier, no. 33, 2011. |

[40] | German Corporate Governance Code, Regierungskommission Deutscher Corporate Governance Kodex, 2017. |

[41] | Asamblea Nacional Constituyente, “Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela 1999,” Gaceta Oficial Extraordinaria, no. 5.453, 24 March 2000. |

[42] | Y. Bermúdez Abreu and C. Prades Espot, “Algunas consideraciones sobre la cogestión laboral en Alemania, España y Venezuela,” Gaceta Laboral, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 293-312, 2006. |

[43] | J. R. Rivero, “Consideraciones sobre la Participación de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras en la Gestión de Empresas,” Aporrea, 22 April 2005. [Online]. Available: https://www.aporrea.org/trabajadores/a13549.html. [Accessed 30 September 2018]. |

[44] | “Ley Orgánica del Trabajo, las Trabajadoras y los Trabajadores,” Gaceta Oficial, no. 6.076, 7 May 2012. |

[45] | C. Hernandez, “Chávez expropia la acería Sidor,” EL PAÍS, 2 May 2008. [Online]. Available: https://elpais.com/internacional/2008/05/02/actualidad/1209679202_850215.html. [Accessed 30 September 2018]. |

[46] | M. I. Cova and J. Dávila, “Participación Directa de los Trabajadores en la Siderúrgica del Orinoco Alfredo Maneiro, Venezuela,” Strategos, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 5-10, 2013. |

[47] | “Nacionalización de Sidor,” YouTube, 16 May 2008. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPC-2eZCReI. [Accessed 1 October 2018]. |

[48] | M. A. Vera Colina, “Cogestión de empresas y transformación del sistema económico en Venezuela: algunas reflexiones,” Gaceta Laboral, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 171-186, 2006. |

[49] | H. Lucena, La Cogestión en Venezuela: orientaciones y lecciones aprendidas, Instituto Latinoamericano de Investigaciones Sociales (ILDIS), 2005. |

[50] | B. Russell, In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays, Routledge, 1935. |

[51] | R. G. Gelos and S.-J. Wei, “Transparency and International Investor Behavior,” NBER Working Paper, no. 9260, 2002. |