The Rise and Fall of RUP: From Industry Standard to Historical Artifact

The software development industry has witnessed one of its most significant paradigm shifts in the early 2000s, when lightweight, agile methodologies like Scrum gradually displaced established heavyweight processes such as the Rational Unified Process (RUP). This transformation represents more than just a change in project management frameworks—it reflects a fundamental evolution in how software teams approach collaboration, risk management, and value delivery in an increasingly dynamic business environment.

The Rational Unified Process emerged in the late 1990s as a comprehensive software development framework that promised to bring order and predictability to complex software projects. Created by Rational Software Corporation (later acquired by IBM), RUP represented the culmination of decades of software engineering best practices, incorporating iterative development, risk management, and architecture-centric approaches. During its heyday in the late 1990s and early 2000s, RUP quickly became the dominant process framework, offering organizations a structured methodology that seemed to address the chaotic nature of software development.

However, by the early 2010s, IBM Rational had effectively retired RUP, marking the end of an era for one of the most influential software development methodologies of its time. This decline coincided with the meteoric rise of agile methodologies, particularly Scrum, which fundamentally challenged RUP’s heavyweight, documentation-intensive approach.

The Historical Context: When Heavyweight Met Lightweight

RUP’s Foundation and Promise

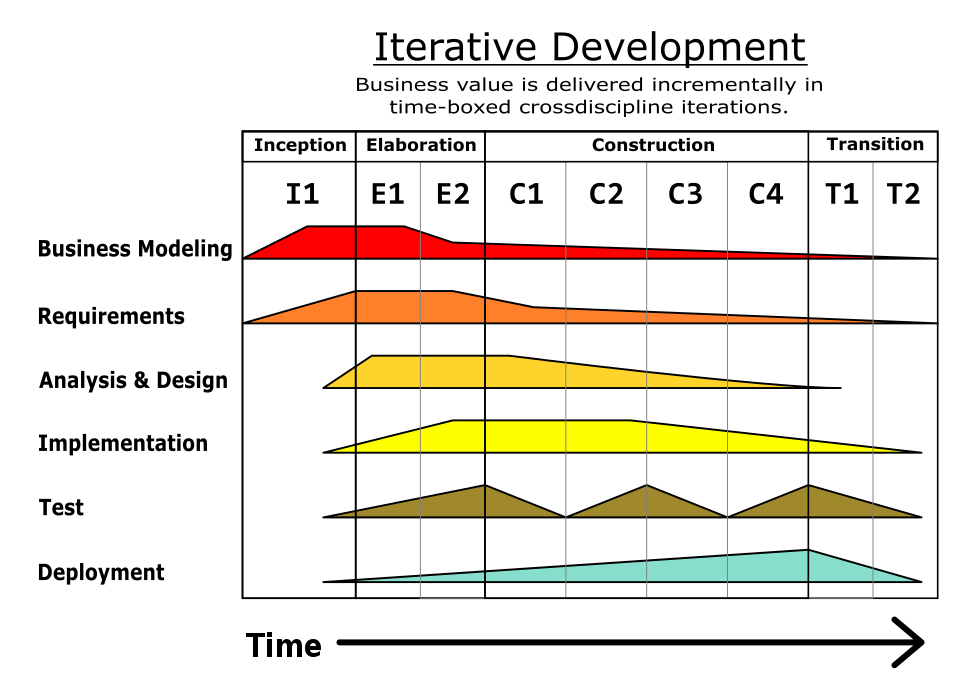

The Rational Unified Process was built upon six fundamental best practices that distinguished it from earlier waterfall approaches: iterative development, requirements management, component-based architecture, visual modeling, quality verification, and change control. The methodology organized software development into four distinct phases—Inception, Elaboration, Construction, and Transition—each designed to systematically address different aspects of the software lifecycle.

RUP’s strength lay in its comprehensive nature. It provided detailed guidance for every aspect of software development, from initial requirements gathering to final deployment and maintenance. This thoroughness made it particularly attractive to large organizations that valued process documentation, regulatory compliance, and predictable project outcomes.

The Seeds of Scrum’s Revolution

Meanwhile, the foundations of Scrum were being laid through very different philosophical principles. In 1993, Jeff Sutherland, John Scumniotales, and Jeff McKenna implemented the first full Scrum process at Easel Corporation, drawing inspiration from a 1986 Harvard Business Review article by Takeuchi and Nonaka that compared product development to rugby. The methodology was formally presented to the public in 1995 when Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber jointly published their paper “The SCRUM Development Process” at the OOPSLA conference.

Scrum’s creators, both Vietnam War veterans, brought a different perspective to software development—one shaped by the need for rapid adaptation and risk assessment in unpredictable environments. Their experiences with corporate frustration and project failures drove them to seek alternatives to the rigid, plan-driven approaches that dominated the industry.

The Agile Manifesto: The Catalyst for Change

The pivotal moment in this transformation came in February 2001, when seventeen software development luminaries, including Sutherland and Schwaber, gathered at Snowbird, Utah, to draft the Agile Manifesto. This document articulated four core values that directly challenged the fundamental assumptions of heavyweight methodologies like RUP:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

The Agile Manifesto represented more than just a new approach to software development—it was a philosophical revolution that prioritized adaptability, customer value, and human collaboration over rigid process adherence.

The Great Divide: Comparing RUP and Scrum Approaches

Process Structure and Flexibility

The fundamental differences between RUP and Scrum became apparent in their approach to process structure. RUP followed a predetermined, end-to-end project management style where each iteration and phase were planned during the earliest stages of the project. This approach provided predictability but often struggled with changing requirements or evolving business needs.

Scrum, in contrast, embraced uncertainty by determining the scope of each sprint only at the end of the previous one. This fundamental difference meant that while RUP teams spent considerable time in upfront planning, Scrum teams could adapt continuously based on emerging insights and changing priorities.

Requirements Management Philosophy

The methodologies also differed significantly in their approach to requirements management. RUP utilized formal risk management approaches, prioritizing requirements with the highest risk exposure first. Requirements were typically represented through coarse-grained use cases that supported comprehensive system modeling but could be cumbersome to modify.

Scrum took a markedly different approach, focusing on requirements that delivered the highest business value and representing them through fine-grained user stories. This approach enabled more immediate responsiveness to changes, as modifications could be incorporated into the next sprint without disrupting the entire project architecture.

Documentation and Communication

One of the most visible differences between the methodologies lay in their approach to documentation. RUP emphasized comprehensive documentation as a means of ensuring knowledge transfer, regulatory compliance, and long-term maintainability. This thorough documentation approach was particularly valuable for complex, process-driven applications typical in industrial environments.

Scrum deliberately minimized documentation in favor of direct communication and working software. The methodology’s emphasis on daily stand-ups, sprint reviews, and retrospectives created multiple touchpoints for knowledge sharing without requiring extensive written documentation.

The Tipping Point: Why Organizations Chose Scrum

Industry Statistics and Adoption Patterns

The shift from RUP to Scrum wasn’t merely philosophical—it was driven by measurable business outcomes. Current industry statistics reveal the extent of this transformation: 86% of software development teams have now adopted agile methodologies, with 81% of agile teams specifically using Scrum or Scrum-based approaches.

The success rate differences between methodologies proved compelling. Agile projects demonstrate a 70% success rate compared to traditional methodologies’ 58% success rate. Furthermore, organizations implementing agile approaches report 60% higher revenue growth than those using traditional methodologies.

Addressing Traditional Methodology Pain Points

RUP’s decline can be attributed to several systemic issues that became increasingly problematic as software development environments grew more dynamic. Research indicates that 64% of budgets spent on traditional methodologies were wasted on developing features that customers neither used nor required. This waste occurred because traditional approaches, including RUP, often resulted in large disconnects between customers and development teams.

The rigidity of traditional methods also created significant challenges. Changes were difficult and costly to implement, often requiring teams to return to much earlier project stages. This inflexibility proved particularly problematic in environments where customer requirements evolved rapidly or where market conditions changed during development cycles.

The Appeal of Scrum’s Simplicity

Scrum’s success stemmed from its ability to address these pain points through elegant simplicity. Rather than prescribing detailed processes for every development scenario, Scrum provided a lightweight framework that teams could adapt to their specific contexts. This adaptability proved particularly valuable for organizations operating in dynamic market conditions.

The methodology’s emphasis on cross-functional teams and collaborative decision-making also resonated with organizations seeking to break down traditional silos. 47% of organizations adopting agile methodologies reported improved communication and collaboration between IT and business teams.

Case Studies: Real-World Transformations

From RUP to Scrum: Global Software Development

Academic research provides concrete evidence of successful transitions from RUP to Scrum. A comprehensive study examining global software development projects found that transitioning from RUP to Scrum brought positive effects in requirements engineering, communication, cost management, and cross-functionality.

The study revealed that Scrum’s approach to requirements management—using fine-grained user stories rather than coarse-grained use cases—enabled teams to respond more effectively to changing requirements in distributed development environments. This flexibility proved particularly valuable for organizations managing development teams across multiple time zones and cultural contexts.

Enterprise Adoption Patterns

Large organizations have increasingly recognized the strategic value of agile transformation. Current data shows that 94% of organizations have been practicing agile methodologies for 1-5 years, with 33% having used agile methods for 3-5 years. This widespread adoption spans beyond software development teams, with 48% of engineering and R&D teams, 28% of business operations, and 20% of marketing teams now employing agile principles.

The transformation has been particularly pronounced in enterprise environments, where 32% of organizations report that business leaders are driving company-wide agile transformations. This represents a fundamental shift from the technical team-driven adoption patterns that characterized early agile implementations.

The Technical and Cultural Dimensions of Change

Process Maturity and Organizational Learning

The transition from RUP to Scrum represented more than just a change in project management tools—it required fundamental shifts in organizational culture and learning approaches. RUP had been designed to support organizations seeking formal process maturity, offering structured pathways to achieve higher capability maturity model (CMM) levels.

Scrum, however, prioritized empirical process control over defined processes, emphasizing continuous improvement through inspection and adaptation. This shift required organizations to develop new competencies in self-organization, cross-functional collaboration, and rapid feedback incorporation.

The Role of Technology Evolution

The technological landscape also contributed to this transformation. The rise of web-based applications, mobile development, and cloud computing created development environments that demanded faster iteration cycles and more frequent deployments. These technical trends aligned naturally with Scrum’s emphasis on short sprints and continuous delivery, while RUP’s longer iteration cycles became increasingly misaligned with market expectations.

Skills and Workforce Development

The methodological shift also impacted workforce development and skills requirements. RUP implementations typically required teams of highly skilled professionals capable of navigating complex process documentation and specialized tools. This requirement created barriers to adoption and limited scalability in resource-constrained environments.

Scrum’s simpler framework reduced barriers to entry while still requiring sophisticated skills in collaboration, communication, and adaptive planning. This balance made agile approaches more accessible to a broader range of development teams while still demanding high levels of professional competency.

The Contemporary Landscape: Scrum’s Dominance and Evolution

Current Market Position

Today’s software development landscape demonstrates Scrum’s complete dominance over traditional heavyweight methodologies. Among agile practitioners, 81% use Scrum or Scrum-based approaches, making it the most widely adopted agile framework. The Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe), which incorporates Scrum principles at enterprise scale, is used by 37% of organizations seeking to implement agile practices across large, complex organizational structures.

Hybrid Approaches and Continued Evolution

Interestingly, the complete displacement of RUP has given way to more nuanced approaches that combine elements from multiple methodologies. Some organizations have developed hybrid models that retain RUP’s emphasis on architecture and documentation while incorporating Scrum’s iterative delivery and collaborative practices.

This evolution suggests that the RUP-to-Scrum transition was not simply about replacing one methodology with another, but about learning to select and combine approaches based on specific project contexts and organizational needs.

Emerging Challenges and Future Directions

Despite Scrum’s widespread success, organizations continue to face challenges in agile implementation. Research indicates that 34% of organizations still encounter resistance to agile adoption, suggesting that cultural transformation remains as important as process change. Additionally, 52% of organizations use agile for more than half of their projects, indicating that selective application rather than universal adoption remains common.

The future likely holds continued evolution rather than another wholesale methodology replacement. Current trends suggest integration of agile principles with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automated development tools, rather than fundamental paradigm shifts comparable to the RUP-to-Scrum transformation.

Lessons Learned: Understanding the Transformation

Why RUP Failed to Adapt

RUP’s decline offers important lessons about methodology sustainability in dynamic environments. The framework suffered from several critical weaknesses that became more pronounced over time:

- Complexity and Overhead: RUP became increasingly unwieldy as Rational and IBM added additional guidance and artifacts to extend its applicability. This expansion made the methodology difficult to understand and apply successfully, particularly for smaller teams or simpler projects.

- Misapplication and Rigidity: RUP was often inappropriately implemented as a waterfall process, with teams treating Inception as a big requirements phase, Elaboration as detailed architecture work, and Transition as a testing phase. This misapplication undermined the methodology’s intended iterative benefits.

- Tool Dependency: RUP’s tight integration with specific tools and platforms created vendor lock-in and reduced flexibility. As development tools evolved rapidly, this dependency became a liability rather than an asset.

Scrum’s Sustainable Success Factors

Scrum’s enduring success can be attributed to several key design principles that have proven resilient across changing technological and business contexts:

- Simplicity and Adaptability: Scrum’s minimalist framework provides structure without prescriptive detail, enabling teams to adapt the methodology to their specific contexts. This adaptability has allowed Scrum to remain relevant across diverse industries and project types.

- Empirical Foundation: Scrum’s emphasis on empirical process control—transparency, inspection, and adaptation—provides a robust foundation for continuous improvement. This approach enables teams to evolve their practices based on experience rather than predetermined assumptions.

- Value-Focused Delivery: Scrum’s emphasis on delivering working software in short iterations aligns naturally with business needs for rapid value realization. This alignment has sustained executive support and resource allocation for agile initiatives.

Conclusion

The transformation from RUP to Scrum represents one of the most significant paradigm shifts in software development history. This change reflected broader industry evolution toward more adaptive, customer-focused, and collaborative approaches to software creation. While RUP served an important role in professionalizing software development and introducing iterative practices, its heavyweight nature ultimately proved incompatible with the dynamic, fast-paced requirements of modern software development.

Scrum’s success lies not just in its technical merits, but in its alignment with fundamental human and business needs for flexibility, transparency, and continuous value delivery. As the software development industry continues to evolve, the principles underlying this transformation—adaptability, customer focus, and empirical learning—remain as relevant as ever.

The RUP-to-Scrum transition offers enduring lessons about the importance of methodological evolution, the dangers of over-complexity, and the value of approaches that empower teams rather than constrain them. These insights continue to inform how organizations approach process improvement and transformation in an ever-changing technological landscape.

References

- Rational Unified Process (RUP) | Research Starters: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/computer-science/rational-unified-process-rup

- Enhancing agile product development with scrum: https://fepbl.com/index.php/estj/article/view/1108/1336

- Scrum versus Rational Unified Process in facing the main challenges: https://orbit.dtu.dk/files/216634691/Final_Scrum_clean.pdf

- How the Rational Unified Process (RUP) Methodology Streamlines Software Development: https://ones.com/blog/rational-unified-process-rup-methodology-streamlines-software-development/

- Why and how is Scrum being adapted in practice: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0164121221002077

- Comparing Scrum, XP, and RUP: Understanding the Key Differences and Similarities: https://www.mobiprep.com/post/comparing-scrum-xp-and-rup-understanding-the-key-differences-and-similarities

- What Happened to the Rational Unified Process (RUP)?: https://scottambler.com/what-happened-to-rup/

- Adopting Agile Scrum: https://digitalcommons.harrisburgu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=%2Fcontext%2Fpmgt_dandt%2Farticle%2F1005%2F&path_info=Chaganti__Anirudh.pdf

- What is the difference between RUP and scrum?: https://www.evozon.com/glossary/methodologies/what-is-the-difference-between-rup-and-scrum/

- What is RUP(Rational Unified Process) and its Phases?: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/software-engineering/rup-and-its-phases/

- Agile vs Scrum: Choosing the Right Methodology for Your Team: https://www.6sigma.us/project-management/agile-vs-scrum/

- Scrum versus Rational Unified Process in facing the main challenges of product configuration systems development (University of Padua): https://www.research.unipd.it/handle/11577/3345021

- How to Fail with the Rational Unified Process: Seven Steps to Pain and Suffering: https://suriweb.com.ar/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/RUP-How-to-fail.pdf

- How Can Agile and Traditional Project Management Coexist?: https://re.public.polimi.it/retrieve/handle/11311/1160935/584019/PostPrint.pdf

- Scrum versus Rational Unified Process in facing the main … (ScienceDirect): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0164121220301643

- Rational unified process (Wikipedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rational_unified_process

- Rational Unified Process (RUP) vs. Scrum: https://study.com/academy/lesson/rational-unified-process-rup-vs-scrum.html

- Rational Unified Process: A Best Practices Approach: https://www.eecg.utoronto.ca/~jacobsen/courses/ece1770/slides/rup.pdf

- Rational Unified Process vs Agile: Which Methodology Accelerates Software Delivery?: https://ones.com/blog/rational-unified-process-vs-agile-accelerating-software-delivery/

- Software Development Methodologies timeline: https://www.officetimeline.com/blog/software-development-methodologies-timeline

- Driving Enterprise Agile Adoption with Jira and Confluence: https://www.catapultlabs.com/blog/driving-enterprise-agile-adoption-with-jira-and-confluence

- Problems with Traditional Methods of Software Development: https://eternalsunshineoftheismind.wordpress.com/2013/03/10/problems-with-traditional-methods-of-software-development/

- The Evolution of Software Development Methodologies: https://xorbix.com/insights/the-evolution-of-software-development-methodologies/

- AWG – A Sustainable Engine for Enterprise Agile Adoption: https://agilealliance.org/awg-a-sustainable-engine-for-enterprise-agile-adoption/

- The End of Traditional Software Development Jobs: What Future?: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/end-traditional-software-development-jobs-what-future-ramachandran-ojsxe

- The Evolution of Software Development Methodologies: https://dev.to/jottyjohn/the-evolution-of-software-development-methodologies-4652

- Adapting Agile for the enterprise: https://www.sap.com/resources/adapting-agile-for-the-enterprise

- How Software Development is Changing Forever, and How You’ll Need to Change With It: https://dev.to/jdbar/how-software-development-is-changing-forever-and-how-youll-need-to-change-with-it-1jih

- Software Development : Evolution to Transformation Journey: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/software-development-evolution-transformation-journey-divyesh-shah-f1efc

- Agile adoption and development trends- Insights into the state of agile in 2024: https://talent500.com/blog/agile-adoption-and-development-trends/

- 10 Frequent Missteps in Applying Software Development Methodologies: https://devot.team/blog/software-development-methodologies

- Agile software development (Wikipedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agile_software_development

- Four Stages of Agile Adoption and Maturity: https://docs.broadcom.com/doc/the-agile-journey-four-stages-of-agile-adoption-and-maturity

- Disruption of Traditional Software Engineering: The Dawn of Intelligent Engineering: http://www.ness.com/automating-software-development

- From Waterfall to DevOps: how approaches to software development have changed: https://playsdev.com/blog/evolution-of-development-methodologies/

- Agile adoption accelerates across the enterprise: https://itnove.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/15th-state-of-agile-report.pdf

- The decline of software engineering jobs—what’s a good pivot?: https://www.reddit.com/r/CasualConversation/comments/1iod243/the_decline_of_software_engineering_jobswhats_a/

- A Brief History of Software Development Methodologies – Growin: https://www.growin.com/blog/history-of-software-development-methodologies/

- Why enterprises are struggling to adopt agile and how to overcome?: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-enterprises-struggling-adopt-agile-how-overcome-jyotiranjan-sahoo

- A Short History Of Scrum: https://www.thescrummaster.co.uk/scrum/short-history-scrum/

- Dive into 60+ Agile Statistics for 2025: https://www.esparkinfo.com/blog/agile-statistics

- The History of Scrum: How, when and why | ScrumDesk: https://www.scrumdesk.com/the-history-of-scrum-how-when-and-why/

- Agile Adoption Statistics: How is Software Development changing?: https://www.simform.com/blog/state-of-agile-adoption/

- The IBM Rational Unified Process: An Enabler for Higher Process Maturity: https://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/rational/web/whitepapers/2003/rup_tp178.pdf

- The History of Scrum: https://www.agile42.com/en/blog/scrum-history

- 50+ Agile Statistics You Need to Know in 2025: https://www.notta.ai/en/blog/agile-statistics

- Jeff Sutherland: https://scrumguides.org/jeff.html

- 55+ Key Agile Development Statistics You Need to Know in 2025: https://tsttechnology.io/blog/agile-development-statistics

- Rational Unified Process – for Systems Engineering RUP: https://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/rational/web/whitepapers/2003/TP165.pdf

- The Scrum Approach to Software Development: https://amslaurea.unibo.it/id/eprint/8255/1/Tesi.pdf

- 101+ Software Development Statistics and Facts 2025: https://www.mindinventory.com/blog/software-development-statistics/

- A Comprehensive Review of RUP (Rational Unified Process) in Software Development: https://www.studocu.vn/vn/document/truong-dai-hoc-kinh-te/business-and-society/a-review-of-rup-rational-unified-process/86674076

- 2020 Scrum Guide: https://scrumguides.org/docs/scrumguide/v2020/2020-Scrum-Guide-US.pdf

- Software Development Statistics for 2025: Trends & Insights: https://www.itransition.com/software-development/statistics

- A Review of RUP (Rational Unified Process): https://www.cscjournals.org/manuscript/Journals/IJSE/Volume5/Issue2/IJSE-142.pdf

- The Origin of Scrum: https://www.visual-paradigm.com/scrum/what-is-the-evolution-of-scrum/

- 17 Agile Statistics You Need to Know in 2025: https://businessmap.io/blog/agile-statistics

- A Comparison between Agile and Traditional Software Development Methodologies: https://globaljournals.org/GJCST_Volume20/2-A-Comparison-between-Agile.pdf

- How IBM Rational Unified Process (RUP) Revolutionizes Software Development: https://ones.com/blog/ibm-rational-unified-process-rup-revolutionizes-software-development-2/

- A Comparative Analysis of Traditional Software Engineering and Agile Software Development: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6480417

- IBM Transitions RUP To RUP 2.0 But Is Not Quite There Yet: https://www.forrester.com/report/IBM+Transitions+RUP+To+RUP+20+But+Is+Not+Quite+There+Yet/-/E-RES56142?aid=AST113845

- A Hybrid Approach Using RUP and Scrum as a Software Development Strategy: https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1554&context=etd

- Comparing Traditional and Agile Software Development Approaches: Case of Personal Extreme Programming: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/icst-18/55910901

- From RUP to Scrum in Global Software Development: A Case Study: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6337395

- A Comparative Analysis of Traditional Software Engineering and Agile Software Development: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6480417/

- Is the Rational Unified Process (RUP) dead?: https://coderanch.com/t/671161/engineering/Rational-Unified-Process-RUP-dead

- From RUP to Scrum in Global Software Development: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1109/ICGSE.2012.11

- From Traditional to Agile Methodologies in Software Project Management Education: A Case Study: https://dl.acm.org/doi/full/10.1145/3702163.3702460

- The History of the Unified Process: https://scottambler.com/unified-process-history/

- A Comparative Research between SCRUM and RUP Using Real Time Embedded Software Development: https://www.computer.org/csdl/proceedings-article/itng/2013/4967a734/12OmNBa2iDN

- Comparison between Agile and Traditional software development methodologies: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/713866

- IBM® Rational Suite® Enterprise: https://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/rational/web/datasheets/2003/d808b-enterpise.pdf

- Embedding Project Management into XP, Scrum and RUP: https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/3459/3222

- Agile vs. Traditional: Key Differences: https://www.upskillist.com/blog/agile-vs-traditional-key-differences/

- Case Studies: Successful Software Implementations that Transformed Organizations: https://vorecol.com/blogs/blog-case-studies-successful-software-implementations-that-transformed-organizations-169824

- Agile Manifesto: https://www.leadertask.com/articles/agile-manifesto

- Cloud transition case study: https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2019-02/8.2.1%20Department%20of%20Local%20Government%20and%20Communities%20-%20Cloud%20Transition%20Case%20Study.pdf

- Method for Robustness Analysis and Technology Forecasting of Software Based Systems: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:215135/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- SaaS Transition: https://serentcapital.com/case/studies/saas-transition/

- Software Research – Accelerating the Advance of Software Development into an Engineering Discipline: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2017/05/09/251_accelerating_the_advance_of_-software_development.pdf

- Now and then: How the world of Agile has changed since the Agile Manifesto: https://bigpicture.one/blog/world-since-agile-manifesto/

- Bespoke Software Case Studies from Transition: https://www.transitioncomputing.com/case-studies

- History of Agile Methodology: How it was Developed?: https://www.knowledgehut.com/blog/agile/history-of-agile

- Seven application modernization case studies: https://vfunction.com/blog/application-modernization-case-study/

- The two paradigms of software development research: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167642318300030

- Agile Manifesto For Software Development: https://www.knowledgetrain.co.uk/agile/agile-project-management/agile-project-management-course/agile-manifesto

- Software Development Process Supported by Business Process Modeling – An Experience Report: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9ca6/d40ec4d86780baf8855fb3e34da3f1c34ec5.pdf

- History: The Agile Manifesto: https://agilemanifesto.org/history.html