Translating high-level strategic thinking into tangible, operational outcomes stands as one of the greatest challenges organizations face. At the pinnacle of the corporate hierarchy, CEOs craft visions that are broad, ambitious, and often abstract, encompassing bold aspirations for growth, innovation, or transformation. Yet the true measure of such strategic intent is its realization in consistent, value-driving actions at every level of the organization. The journey from a single, overarching strategy to coordinated, impactful activities is a complex process of alignment, translation, and execution—requiring both artful leadership and systematic methods. This article examines, with a particular focus on academic literature and established frameworks, how CEO-level strategy cascades down through portfolios, programs, projects, and activities, ensuring organizational coherence and strategic agility throughout.

The Nature of CEO-Level Strategy

CEO-level strategy is the highest form of intent in an organization, often expressed in a vision, mission statement, or a set of strategic objectives. Unlike operational plans, a CEO’s strategy does not stipulate detailed steps but instead outlines the organization’s long-term direction, competitive position, and aspirations. CEO strategies are characterized by ambiguity, breadth, and the need for interpretation at lower levels of the organization, as these strategies are rarely actionable without further breakdown. Indeed, in their review of strategic management processes, Grant (2016) and Nag, Hambrick, and Chen (2007) emphasize that CEO-level decisions center on resource allocation, competitive scope, and organizational posture—decisions that require translation into executable initiatives.

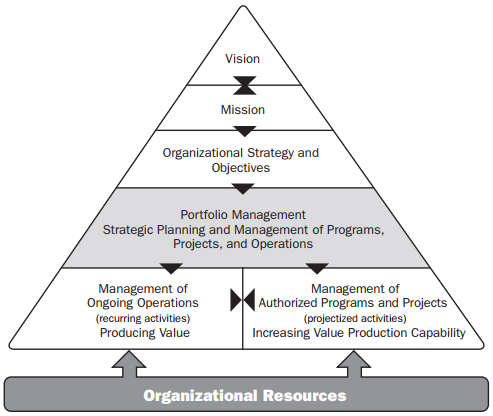

To realize such high-level strategies, organizations turn to a well-established chain of mechanisms: portfolios, programs, projects, and activities. Each acts as a step in decomposing abstract intentions into coordinated work and measurable results.

From Strategy to Portfolio: Bridging Vision and Investment

The first translation of strategy occurs at the portfolio level. A portfolio is not merely a collection of projects or programs; instead, it serves as the organizational mechanism that aligns investment decisions with strategic objectives. PMI’s “The Standard for Portfolio Management” (4th Edition) defines a portfolio as “projects, programs, subsidiary portfolios, and operations managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives.” By organizing work at the portfolio level, organizations can prioritize resource allocation and ensure that every significant initiative demonstrably advances the overarching strategy.

Academic research consistently emphasizes that the portfolio level is where the “strategic fit” is maximized. In their extensive study on portfolio management, Müller, Martinsuo, and Blomquist (2008) show that successful portfolios contain selection mechanisms ensuring projects and programs align with strategy, optimize value, and balance risk. Further, Jonas (2010) proposes that portfolio management is critical for addressing project interdependencies, managing resource bottlenecks, and maintaining strategic coherence as organizations scale. Portfolios thus perform a “translation” role—they interpret CEO ambitions into bundles of initiatives, prioritizing those likely to deliver maximum strategic impact.

Source: The Standard for Portfolio Management (4th Edition)

Programs as Vehicles for Strategy Realization

Portfolios, while strategically focused, remain management constructs; programs, by contrast, are vehicles for execution. A program consists of related projects and initiatives managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits and control not possible from managing them individually. The value of program management lies in its focus on outcomes and benefits realization, rather than the delivery of individual outputs. As Maylor, Brady, Cook-Davies, and Hodgson (2006) observe, programs are inherently strategic, tasked with delivering capabilities that directly advance organizational strategy.

One of the distinguishing features of program management, as Turner and Müller (2003) identify, is its emphasis on managing change and ambiguity. Programs are not simply large projects—they are clusters of related projects with a central integrative logic that connects them to strategic objectives. Pellegrinelli, Partington, Hemingway, Mohdzain, and Shah (2007) reinforce this, arguing that the program manager’s role is to maintain alignment between unfolding project work and evolving strategic intent. Academic frameworks, such as Office of Government Commerce’s (OGC) Managing Successful Programmes (MSP), further codify the role of program management in translating high-level objectives into coordinated transformational activities.

Projects: Tactical Engines of Strategy

If portfolios select what is most important and programs shape broad initiatives, projects deliver the tangible outputs and products that collectively realize strategic objectives. Project management is the focal point where strategic plans meet operational reality. Turner (2009) and PMI’s “A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge” (PMBOK® Guide) define a project as a temporary endeavor with a specific beginning and end, undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.

Projects are inherently tactical, yet their significance for strategy cannot be overstated. As Hobbs and Aubry (2007) demonstrate, the proliferation of project-based work in organizations is a response to the need for flexibility, adaptability, and rapid implementation of strategic intent. Morris and Jamieson (2005) discuss “project strategy” as the bridge between project plans and corporate strategy—project managers must continually interpret and adapt strategic requirements within their scope, making resource and design choices that are relevant to the organization’s larger goals. In effect, every project can be viewed as a microcosm of strategic realization: its success or failure collectively determines the organization’s ability to achieve its CEO’s vision.

Activities: Operationalizing the Strategy

Activities are the most granular level in this decomposition—a level sometimes undervalued in strategy discussions but absolutely vital to success. Activities consist of the specific, day-to-day tasks and actions performed by individuals and teams. No matter how rigorous the strategic planning or how robust the program and project structures, strategies only achieve results when embodied in the habitual practices and coordinated workflows of the organization.

Academic perspectives, such as those articulated by Mintzberg (1994) and Jarzabkowski (2005), assert that strategy is, in many respects, enacted through everyday activity. The term “strategy-as-practice” has emerged to describe how managers and employees translate formal plans into situated decisions and actions. There’s a need for feedback loops from the activity level to ensure strategy remains relevant and responsive to operational realities. Thus, execution at the activity level is not just blind adherence to plans, but involves continuous interpretation, adaptation, and realignment.

Ensuring Alignment: Processes, Roles, and Feedback

Moving from vision to activity is not simply about cascading orders or breaking down work—it demands iterative alignment, governance, and feedback. Strategy must be constantly interpreted and reinterpreted as it traverses each organizational layer. Too rigid a structure can suffocate creativity and responsiveness; too little structure leads to drift and incoherence. The balance is achieved through an interplay of formal processes and informal practices.

One important mechanism is the use of governance frameworks, highlighted in studies by Joslin and Müller (2016) and the empirical analyses of Aubry, Hobbs, and Thuillier (2007). Governance ensures not just compliance but also promotes learning, escalation of issues, and effective decision-making. Regular portfolio and program reviews, stage-gate processes in projects, and performance monitoring at the activity level all serve to keep efforts aligned with shifting strategic priorities. Feedback mechanisms ensure that insights and signals from lower organizational levels can trigger strategy refinement at the top.

Key roles, notably those of portfolio managers, program managers, and project managers, become essential translators of intent. Research by Too and Weaver (2014) demonstrates that their skill in interpreting, communicating, and adapting strategy is critical—without such translation, “strategic intent” is neither actionable nor sustainable.

Integrative Models and Contemporary Challenges

Numerous integrative models have been developed to codify the relationship between strategy and execution. Kaplan and Norton’s “Balanced Scorecard” links high-level objectives to operational measures through a performance management system. Mankins and Steele (2005) emphasize the “strategy-to-execution gap,” recommending that organizations reduce ambiguity at each step and reinforce connectivity through clear metrics and accountability.

A related body of research deals with the contemporary challenges of agility and digital transformation. Geraldi, Maylor, and Williams (2011) argue that as organizations become more projectified and digitally enabled, traditional linear cascades of strategy are increasingly replaced by iterative, feedback-rich models that support agility without losing coherence. This is particularly salient in dynamic environments where strategy itself evolves rapidly in response to market shifts and technological advances.

Case Illustration: Strategy Implementation in Practice

To illustrate, consider a manufacturing company facing intense competition, whose CEO articulates a strategic vision centered on digital transformation and operational excellence. At the portfolio level, executives might prioritize investments into automation, new product development, and supply chain optimization. Key programs are then launched, such as a multi-year digital platform rollout, lean manufacturing initiatives, and expansion into adjacent markets. Within the digital program, projects are initiated to implement an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, develop IoT-enabled products, and train staff in digital skills. Each project, in turn, generates work packages and tasks—the activities—assigned to teams ranging from software engineers to assembly-line workers.

Throughout this process, ongoing reviews, governance checkpoints, and dynamic feedback from performance data ensure alignment with strategic goals. Adaptations at the project or activity level—say, the adoption of a different technical solution or process improvement—are communicated upwards, prompting portfolio or even strategic adjustments as necessary. Scholarly studies, such as those by Blomquist and Müller (2006) and Martinsuo (2013), reveal that such dynamic, multi-level alignment is key to high-performing organizations.

Skill Development and Organizational Culture

Effectively breaking down CEO-level strategy is not only a matter of processes but also hinges upon skill development and cultural factors. Structures and governance alone cannot compensate for a lack of strategic awareness or an engagement deficit at lower organizational levels. Literature on the “middle manager” role, notably Wooldridge, Schmid, and Floyd (2008), shows that empowering managers to act as strategy champions, rather than mere executors, promotes proactive adaptation and robust alignment.

Culture is equally important. Organizations celebrated for executional excellence—Toyota, 3M, or Procter & Gamble, for example—embed strategic priorities in everyday routines, rewards systems, and symbolic actions. Sull, Homkes, and Sull (2015) found that such organizations succeeded by creating line-of-sight between daily work and enterprise goals, using narratives, recognition, and transparent measurement to motivate action. Contemporary research on agile organizations and “strategy as learning” further underscores the value of continuous skill acquisition, cross-functional collaboration, and psychological safety.

The Digital Age: Evolving Approaches

Emerging research details how digital transformation is changing the way organizations cascade strategy. The rise of data analytics, real-time dashboards, and collaboration tools has created new pathways for strategic translation. Decision-making can be distributed further down the hierarchy, and frontline staff can respond faster to changing conditions, closing the gap between intent and action. Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) describe this as an era of “digital superpowers”—where strategic action is increasingly informed by instant feedback and data-driven experimentation.

However, the fundamentals endure: without clarity of purpose, robust governance, and an engaged workforce, the proliferation of new tools risks diffusing rather than reinforcing strategic alignment. Digital platforms can amplify both excellence and dysfunction.

Conclusion: The Art and Science of Strategic Implementation

Translating a CEO’s strategy into activities that drive sustainable organizational value is a core competence and a defining challenge for modern enterprises. Academic and practitioner research alike stress the importance of a deliberate, multi-level process—one that attends equally to clear structures, dynamic feedback, skill development, and organizational culture. While the specific models and tools may evolve, the central lesson remains: strategy must be continuously interpreted, adapted, and enacted at every level of the organization.

Strategic alignment is not achieved through decrees or rigid plans but instead through ongoing dialogue, disciplined execution, and shared purpose. Portfolio management provides the strategic lens; programs integrate and orchestrate complexity; projects deliver the targeted outputs; and activities embody the everyday discipline of execution. The organizations that master this cascade—through formal governance, empowered middle managers, a culture of engagement, and intelligent use of digital tools—are those best positioned not only to survive but to thrive amid uncertainty and change.

References

- Aubry, M., Hobbs, B., & Thuillier, D. (2007). “A New Framework for Understanding Organizational Project Management Through the PMO.” International Journal of Project Management, 25(4), 328-336.

- Blomquist, T., & Müller, R. (2006). “Practices, Roles, and Responsibilities of Middle Managers in Program and Portfolio Management.” Project Management Journal, 37(1), 52-66.

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. Norton.

- Geraldi, J., Maylor, H., & Williams, T. (2011). “Now, Let’s Make It Really Complex (Complicated): A Systematic Review of the Project Complexity Literature.” International Journal of Project Management, 29(9), 1065-1076.

- Grant, R.M. (2024). Contemporary Strategy Analysis. Wiley.

- Hobbs, B., & Aubry, M. (2007). “A Multi-Phase Research Program Investigating Project Management Offices (PMOs): The Results of Phase 1.” Project Management Journal, 38(1), 74-86.

- Jarzabkowski, P. (2005). Strategy as Practice: An Activity-Based Approach. Sage.

- Jonas, D. (2010). “Empowering Project Portfolio Managers: How Management Involvement Impacts Project Portfolio Management Performance.” International Journal of Project Management, 28(8), 818-831.

- Joslin, R., & Müller, R. (2016). “The Relationship Between Project Governance and Project Success.” International Journal of Project Management, 34(4), 613-626.

- Kaplan, R.S., & Norton, D.P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. Harvard Business School Press.

- Mankins, M.C., & Steele, R. (2005). “Turning Great Strategy into Great Performance.” Harvard Business Review, 83(7), 64-72.

- Martinsuo, M. (2013). “Project Portfolio Management in Practice and in Context.” International Journal of Project Management, 31(6), 794-803.

- Maylor, H., Brady, T., Cook-Davies, T., & Hodgson, D. (2006). “From Projectification to Programmification.” International Journal of Project Management, 24(8), 663-674.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. Free Press.

- Morris, P.W.G., & Jamieson, A. (2005). Moving from Corporate Strategy to Project Strategy. PMI.

- Müller, R., Martinsuo, M., & Blomquist, T. (2008). “Project Portfolio Control and Portfolio Management Performance in Different Contexts.” Project Management Journal, 39(3), 28-42.

- Nag, R., Hambrick, D.C., & Chen, M. (2007). “What Is Strategic Management, Really? Inductive Derivation of a Consensus Definition of the Field.” Strategic Management Journal, 28(9), 935-955.

- Pellegrinelli, S., Partington, D., Hemingway, C., Mohdzain, Z., & Shah, M. (2007). “The Importance of Context in Programme Management: An Empirical Review of Programme Practices.” International Journal of Project Management, 25(1), 41-55.

- Project Management Institute (PMI). (2017). The Standard for Portfolio Management (4th Edition).

- Project Management Institute (PMI). (2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) (7th Edition).

- Sull, D., Homkes, R., & Sull, C. (2015). “Why Strategy Execution Unravels—and What to Do About It.” Harvard Business Review, 93(3), 58-66.

- Too, E.G., & Weaver, P. (2014). “The Management of Project Management: A Conceptual Framework for Project Governance.” International Journal of Project Management, 32(8), 1382-1394.

- Turner, J.R., & Müller, R. (2003). “On the Nature of the Project as a Temporary Organization.” International Journal of Project Management, 21(1), 1-8.

- Turner, J.R. (2009). Handbook of Project-Based Management. McGraw Hill.

- Wooldridge, B., Schmid, T., & Floyd, S.W. (2008). “The Middle Management Perspective on Strategy Process: Contributions, Synthesis, and Future Research.” Journal of Management, 34(6), 1190-1221.